Child Care Disruptions

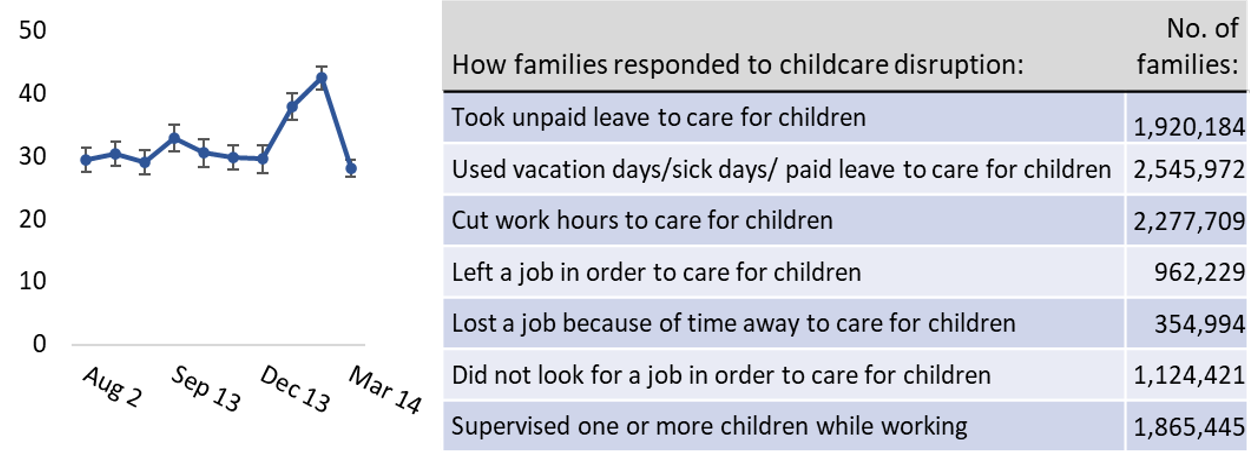

Child care disruptions have declined since the Omicron surge but 28% of adults with young children still reported a disruption last month.

Child care disruptions, March 2 - 14, 2022

Percent of households where children < 5 years were unable to attend child care in last 4 weeks

Source: Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Note: Universe is adults in households with children under 5 years of age.

Though child care disruptions have declined, families with children under 5 still face difficult child care decisions. Nearly 3 in 10 adults experienced a child care disruption at some point during the 4 weeks ending March 14, 2022. While more than 2 million parents cut their work hours to care for children, and 1.9 million parents took unpaid leave, nearly 1 million left a job, and another 355,000 lost a job because of child care disruptions.

The impact on careers, the workforce, and mental health for both parents and children are not trivial. Women have disproportionately managed households and child care concerns during the pandemic and were more likely to cut hours and leave their jobs (Employment Rates).1 A daycare center in Louisville, Kentucky saw enrollment drop by half as women leaving the workforce no longer needed care or lost their eligibility for it.2 As disruptions became common, children were more likely to experience behavioral issues, at least partly in response to parental stress and anxiety from the increased difficulty of balancing work and family (Mental Health Providers).3

Child care disruptions due to the pandemic have heightened the inequities faced by low-income families. Soaring child care costs and daycare closures have been hardest on low-income families, who were also more likely to experience job loss at the start of the pandemic.4,5,6 In interviews with the Washington Post, parents from low-income families describe a series of consequences due to child care disruptions, including unpaid leave from low-wage hourly jobs, using credit cards and other forms of debt to make ends meet and, in some cases, being let go from work.7

While Covid relief dollars have helped to shore up the sector, these are only temporary solutions. Long-term investments in child care are a critical step in stabilizing the workforce.

“Gender differences in couples’ division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19”. Zamarro, Prados. Review of Economics of the Household. January, 2021. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7

“COVID drastically reduced a Louisville child care center’s enrollment, but not its spirit”. Ladd, Tobin. Louisville Courier Journal. April, 2022. https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2022/04/07/louisville-child-care-center-battles-worker-shortage-declining-enrollment/7246818001/

“Effects of Daily School and Care Disruptions During the Covid-19 Pandemic on Child Mental Health”. Gassman-Pines, Ananat, Fitz-Henley II, and Leer. National Bureau of Economic Research. January, 2022. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29659/w29659.pdf

“Covid-19 Pulse Survey Data”. Health Resources & Services Administration. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/covid-19/data

“Costly and Unavailable: America Lacks Sufficient Child Care Supply for Infants and Toddlers”. Jessen-Howard, Malik, and Falgout. Center for American Progress. August, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/costly-unavailable-america-lacks-sufficient-child-care-supply-infants-toddlers/

“Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession”. Gould, Kassa. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/

“For low-income parents, no day care often means no pay”. Bhattarai, Flowers. The Washington Post. February, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/02/22/child-care-covid-inequality/